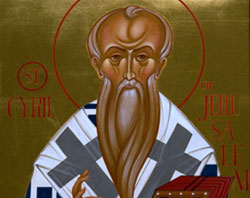

Our attention today is focused on St Cyril of Jerusalem. His life is woven of two dimensions: on the one hand, pastoral care, and on the other, his involvement, in spite of himself, in the heated controversies that were then tormenting the Church of the East.

Cyril was born at or near Jerusalem in 315 A.D. He received an excellent literary education which formed the basis of his ecclesiastical culture, centred on study of the Bible. He was ordained a priest by Bishop Maximus.

When this Bishop died or was deposed in 348, Cyril was ordained a Bishop by Acacius, the influential Metropolitan of Caesarea in Palestine, a philo-Arian who must have been under the impression that in Cyril he had an ally; so as a result Cyril was suspected of having obtained his episcopal appointment by making concessions to Arianism.

Actually, Cyril very soon came into conflict with Acacius, not only in the field of doctrine but also in that of jurisdiction, because he claimed his own See to be autonomous from the Metropolitan See of Caesarea.

Cyril was exiled three times within the course of approximately 20 years: the first time was in 357, after being deposed by a Synod of Jerusalem; followed by a second exile in 360, instigated by Acacius; and finally, in 367, by a third exile – his longest, which lasted 11 years – by the philo-Arian Emperor Valens.

It was only in 378, after the Emperor’s death, that Cyril could definitively resume possession of his See and restore unity and peace to his faithful.

Some sources of that time cast doubt on his orthodoxy, whereas other equally ancient sources come out strongly in his favour. The most authoritative of them is the Synodal Letter of 382 that followed the Second Ecumenical Council of Constantinople (381), in which Cyril had played an important part.

In this Letter addressed to the Roman Pontiff, the Eastern Bishops officially recognized Cyril’s flawless orthodoxy, the legitimacy of his episcopal ordination and the merits of his pastoral service, which ended with his death in 387.

Of Cyril’s writings, 24 famous catecheses have been preserved, which he delivered as Bishop in about 350.

Introduced by a Procatechesis of welcome, the first 18 of these are addressed to catechumens or candidates for illumination (photizomenoi) [candidates for Baptism]; they were delivered in the Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre. Each of the first ones (nn. 1-5) respectively treat the prerequisites for Baptism, conversion from pagan morals, the Sacrament of Baptism, the 10 dogmatic truths contained in the Creed or Symbol of the faith.

The next catecheses (nn. 6-18) form an “ongoing catechesis” on the Jerusalem Creed in anti-Arian tones.

Of the last five so-called “mystagogical catecheses”, the first two develop a commentary on the rites of Baptism and the last three focus on the Chrism, the Body and Blood of Christ and the Eucharistic Liturgy. They include an explanation of the Our Father (Oratio dominica).

This forms the basis of a process of initiation to prayer which develops on a par with the initiation to the three Sacraments of Baptism, Confirmation and the Eucharist.

The basis of his instruction on the Christian faith also served to play a polemic role against pagans, Judaeo Christians and Manicheans. The argument was based on the fulfilment of the Old Testament promises, in a language rich in imagery.

Catechesis marked an important moment in the broader context of the whole life – particularly liturgical – of the Christian community, in whose maternal womb the gestation of the future faithful took place, accompanied by prayer and the witness of the brethren.

Taken as a whole, Cyril’s homilies form a systematic catechesis on the Christian’s rebirth through Baptism.

Taken as a whole, Cyril’s homilies form a systematic catechesis on the Christian’s rebirth through Baptism.

He tells the catechumen: “You have been caught in the nets of the Church (cf. Mt 13: 47). Be taken alive, therefore; do not escape for it is Jesus who is fishing for you, not in order to kill you but to resurrect you after death. Indeed, you must die and rise again (cf. Rom 6: 11, 14)…. Die to your sins and live to righteousness from this very day” (Procatechesis, 5).

From the doctrinal viewpoint, Cyril commented on the Jerusalem Creed with recourse to the typology of the Scriptures in a “symphonic” relationship between the two Testaments, arriving at Christ, the centre of the universe.

The typology was to be described decisively by Augustine of Hippo: “In the Old Testament there is a veiling of the New, and in the New Testament there is a revealing of the Old” (De catechizandis rudibus 4, 8).

As for the moral catechesis, it is anchored in deep unity to the doctrinal catechesis: the dogma progressively descends in souls who are thus urged to transform their pagan behaviour on the basis of new life in Christ, a gift of Baptism.

The “mystagogical” catechesis, lastly, marked the summit of the instruction that Cyril imparted, no longer to catechumens but to the newly baptized or neophytes during Easter week. He led them to discover the mysteries still hidden in the baptismal rites of the Easter Vigil.

Enlightened by the light of a deeper faith by virtue of Baptism, the neophytes were at last able to understand these mysteries better, having celebrated their rites.

Especially with neophytes of Greek origin, Cyril made use of the faculty of sight which they found congenial. It was the passage from the rite to the mystery that made the most of the psychological effect of amazement, as well as the experience of Easter night.

Here is a text that explains the mystery of Baptism: “You descended three times into the water, and ascended again, suggesting by a symbol the three days burial of Christ, imitating Our Saviour who spent three days and three nights in the heart of the earth (cf. Mt 12: 40). Celebrating the first emersion in water you recall the first day passed by Christ in the sepulchre; with the first immersion you confessed the first night passed in the sepulchre: for as he who is in the night no longer sees, but he who is in the day remains in the light, so in the descent, as in the night, you saw nothing, but in ascending again you were as in the day. And at the self-same moment you were both dying and being born; and that water of salvation was at once your grave and your mother…. For you… the time to die goes hand in hand with the time to be born: one and the same time effected both of these events” (cf. Second Mystagogical Catechesis, n. 4).

The mystery to be understood is God’s plan, which is brought about through Christ’s saving actions in the Church.

In turn, the mystagogical dimension is accompanied by the dimension of symbols which express the spiritual experience they “explode”. Thus, Cyril’s catechesis, on the basis of the three elements described – doctrinal, moral and lastly, mystagogical – proves to be a global catechesis in the Spirit.

The mystagogical dimension brings about the synthesis of the two former dimensions, orienting them to the sacramental celebration in which the salvation of the whole human person takes place.

In short, this is an integral catechesis which, involving body, soul and spirit – remains emblematic for the catechetical formation of Christians today.

expressed in images and symbols taken from nature, daily life and the Bible. Ephrem gives his poetry and liturgical hymns a didactic and catechetical character: they are theological hymns yet at the same time suitable for recitation or liturgical song. On the occasion of liturgical feasts, Ephrem made use of these hymns to spread Church doctrine. Time has proven them to be an extremely effective catechetical instrument for the Christian community.