Dominican Tertiary, born at Siena, 25 March, 1347; died at Rome, 29 April, 1380.

From the Catholic Encyclopedia, found at New Advent –

She was the youngest one of a very large family. Her father, Giacomo di Benincasa, was a dyer; her mother, Lapa, the daughter of a local poet. They belonged to the lower middle-class faction of tradesmen and petty notaries, known as “the Party of the Twelve”, which between one revolution and another ruled the Republic of Siena from 1355 to 1368. From her earliest childhood Catherine began to see visions and to practise extreme austerities. At the age of seven she consecrated her virginity to Christ; in her sixteenth year she took the habit of the Dominican Tertiaries, and renewed the life of the anchorites of the desert in a little room in her father’s house. After three years of celestial visitations and familiar conversation with Christ, she underwent the mystical experience known as the “spiritual espousals”, probably during the carnival of 1366. She now rejoined her family, began to tend the sick, especially those afflicted with the most repulsive diseases, to serve the poor, and to labour for the conversion of sinners.Though always suffering terrible physical pain, living for long intervals on practically no food save the Blessed Sacrament, she was ever radiantly happy and full of practical wisdom no less than the highest spiritual insight. All her contemporaries bear witness to her extraordinary personal charm, which prevailed over the continual persecution to which she was subjected even by the friars of her own order and by her sisters in religion.

She began to gather disciples round her, both men and women, who formed a wonderful spiritual fellowship, united to her by the bonds of mystical love. During the summer of 1370 she received a series of special manifestations of Divine mysteries, which culminated in a prolonged trance, a kind of mystical death, in which she had a vision of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, and heard a Divine command to leave her cell and enter the public life of the world. She began to dispatch letters to men and women in every condition of life, entered into correspondence with the princes and republics of Italy, was consulted by the papal legates about the affairs of the Church, and set herself to heal the wounds of her native land by staying the fury of civil war and the ravages of faction. She implored the pope, Gregory XI, to leave Avignon, to reform the clergy and the administration of the Papal States, and ardently threw herself into his design for a crusade, in the hopes of uniting the powers of Christendom against the infidels, and restoring peace to Italy by delivering her from the wandering companies of mercenary soldiers. While at Pisa, on the fourth Sunday of Lent, 1375, she received the Stigmata, although, at her special prayer, the marks did not appear outwardly in her body while she lived.

Mainly through the misgovernment of the papal officials, war broke out between Florence and the Holy See, andalmost the whole of the Papal States rose in insurrection. Catherine had already been sent on a mission from the pope to secure the neutrality of Pisa and Lucca.

In June, 1376, she went to Avignon as ambassador of the Florentines, to make their peace; but, either through the bad faith of the republic or through a misunderstanding caused by the frequent changes in its government, she was unsuccessful. Nevertheless she made such a profound impression upon the mind of the pope, that, in spite of the opposition of the French king and almost the whole of the Sacred College, he returned to Rome (17 January, 1377).

Catherine spent the greater part of 1377 in effecting a wonderful spiritual revival in the country districts subject to the Republic of Siena, and it was at this time that she miraculously learned to write, though she still seems to have chiefly relied upon her secretaries for her correspondence. Early in 1378 she was sent by Pope Gregory to Florence, to make a fresh effort for peace. Unfortunately, through the factious conduct of her Florentine associates, she became involved in the internal politics of the city, and during a popular tumult (22 June) an attempt was made upon her life. She was bitterly disappointed at her escape, declaring that her sins had deprived her of the red rose of martyrdom. Nevertheless, during the disastrous revolution known as “the tumult of the Ciompi”, she still remained at Florence or in its territory until, at the beginning of August, news reached the city that peace had been signed between the republic and the new pope. Catherine then instantly returned to Siena, where she passed a few months of comparative quiet, dictating her “Dialogue”, the book of her meditations and revelations.

In the meanwhile the Great Schism had broken out in the Church. From the outset Catherine enthusiastically adhered to the Roman claimant, Urban VI, who in November, 1378, summoned her to Rome. In the Eternal City she spent what remained of her life, working strenuously for the reformation of the Church, serving the destitute and afflicted, and dispatching eloquent letters in behalf of Urban to high and low in all directions. Her strength was rapidly being consumed; she besought her Divine Bridegroom to let her bear the punishment for all the sins of the world, and to receive the sacrifice of her body for the unity and renovation of the Church; at last it seemed to her that the Bark of Peter was laid upon her shoulders, and that it was crushing her to death with its weight. After a prolonged and mysterious agony of three months, endured by her with supreme exultation and delight, from Sexagesima Sunday until the Sunday before the Ascension, she died. Her last political work, accomplished practically from her death-bed, was the reconciliation of Pope Urban VI with the Roman Republic (1380).

Among Catherine’s principal followers were Fra Raimondo delle Vigne, of Capua (d. 1399), her confessor and biographer, afterwards General of the Dominicans, and Stefano di Corrado Maconi (d. 1424), who had been one of her secretaries, and became Prior General of the Carthusians. Raimondo’s book, the “Legend”, was finished in 1395. A second life of her, the “Supplement”, was written a few years later by another of her associates, Fra Tomaso Caffarini (d. 1434), who also composed the “Minor Legend”, which was translated into Italian by Stefano Maconi. Between 1411 and 1413 the depositions of the surviving witnesses of her life and work were collected at Venice, to form the famous “Process”. Catherine was canonized by Pius II in 1461. The emblems by which she is known in Christian art are the lily and book, the crown of thorns, or sometimes a heart–referring to the legend of her having changed hearts with Christ. Her principal feast is on the 30th of April, but it is popularly celebrated in Siena on the Sunday following. The feast of her Espousals

is kept on the Thursday of the carnival.

The works of St. Catherine of Siena rank among the classics of the Italian language, written in the beautiful Tuscan vernacular of the fourteenth century. Notwithstanding the existence of many excellent manuscripts, the printed editions present the text in a frequently mutilated and most unsatisfactory condition. Her writings consist of

the “Dialogue”, or “Treatise on Divine Providence”;

a collection of nearly four hundred letters; and

a series of “Prayers”.The “Dialogue” especially, which treats of the whole spiritual life of man in the form of a series of colloquies between the Eternal Father and the human soul (represented by Catherine herself), is the mystical counterpart in prose of Dante’s “Divina Commedia”.

A smaller work in the dialogue form, the “Treatise on Consummate Perfection”, is also ascribed to her, but is probably spurious. It is impossible in a few words to give an adequate conception of the manifold character and contents of the “Letters”, which are the most complete expression of Catherine’s many-sided personality. While those addressed to popes and sovereigns, rulers of republics and leaders of armies, are documents of priceless value to students of history, many of those written to private citizens, men and women in the cloister or in the world, are as fresh and illuminating, as wise and practical in their advice and guidance for the devout Catholic today as they were for those who sought her counsel while she lived. Others, again, lead the reader to mystical heights of contemplation, a rarefied atmosphere of sanctity in which only the few privileged spirits can hope to dwell. The key-note to Catherine’s teaching is that man, whether in the cloister or in the world, must ever abide in the cell of self-knowledge, which is the stable in which the traveller through time to eternity must be born again.

More on St. Catherine of Siena

doctor of the church

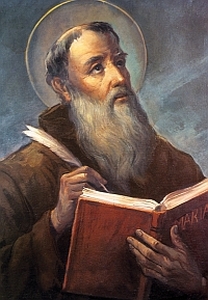

St. Peter Damien, the lowliest servant of the monks, doctor of the Church

Saint Peter Damian

from Vatican.va

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

During the Catecheses of these Wednesdays I am commenting on several important people in the life of the Church from her origins. Today I would like to reflect on one of the most significant figures of the 11th century, St Peter Damian, a monk, a lover of solitude and at the same time a fearless man of the Church, committed personally to the task of reform, initiated by the Popes of the time. He was born in Ravenna in 1007, into a noble family but in straitened circumstances. He was left an orphan and his childhood was not exempt from hardships and suffering, although his sister Roselinda tried to be a mother to him and his elder brother, Damian, adopted him as his son. For this very reason he was to be called Piero di Damiano, Pier Damiani [Peter of Damian, Peter Damian]. He was educated first at Faenza and then at Parma where, already at the age of 25, we find him involved in teaching. As well as a good grounding in the field of law, he acquired a refined expertise in the art of writing the ars scribendi and, thanks to his knowledge of the great Latin classics, became “one of the most accomplished Latinists of his time, one of the greatest writers of medieval Latin”

He distinguished himself in the widest range of literary forms: from letters to sermons, from hagiographies to prayers, from poems to epigrams. His sensitivity to beauty led him to poetic contemplation of the world. Peter Damian conceived of the universe as a never-ending “parable” and a sequence of symbols on which to base the interpretation of inner life and divine and supra-natural reality. In this perspective, in about the year 1034, contemplation of the absolute of God impelled him gradually to detach himself from the world and from its transient realties and to withdraw to the Monastery of Fonte Avellana. It had been founded only a few decades earlier but was already celebrated for its austerity. For the monks’ edification he wrote the Life of the Founder, St Romuald of Ravenna, and at the same time strove to deepen their spirituality, expounding on his ideal of eremitic monasticism.

He distinguished himself in the widest range of literary forms: from letters to sermons, from hagiographies to prayers, from poems to epigrams. His sensitivity to beauty led him to poetic contemplation of the world. Peter Damian conceived of the universe as a never-ending “parable” and a sequence of symbols on which to base the interpretation of inner life and divine and supra-natural reality. In this perspective, in about the year 1034, contemplation of the absolute of God impelled him gradually to detach himself from the world and from its transient realties and to withdraw to the Monastery of Fonte Avellana. It had been founded only a few decades earlier but was already celebrated for its austerity. For the monks’ edification he wrote the Life of the Founder, St Romuald of Ravenna, and at the same time strove to deepen their spirituality, expounding on his ideal of eremitic monasticism.

One detail should be immediately emphasized: the Hermitage at Fonte Avellana was dedicated to the Holy Cross and the Cross was the Christian mystery that was to fascinate Peter Damian more than all the others. “Those who do not love the Cross of Christ do not love Christ”, he said (Sermo XVIII, 11, p. 117); and he described himself as “Petrus crucis Christi servorum famulus Peter, servant of the servants of the Cross of Christ” (Ep, 9, 1). Peter Damian addressed the most beautiful prayers to the Cross in which he reveals a vision of this mystery which has cosmic dimensions for it embraces the entire history of salvation: “O Blessed Cross”, he exclaimed, “You are venerated, preached and honoured by the faith of the Patriarchs, the predictions of the Prophets, the senate that judges the Apostles, the victorious army of Martyrs and the throngs of all the Saints” (Sermo XLVII, 14, p. 304). Dear Brothers and Sisters, may the example of St Peter Damian spur us too always to look to the Cross as to the supreme act God’s love for humankind of God, who has given us salvation.

This great monk compiled a Rule for eremitical life in which he heavily stressed the “rigour of the hermit”: in the silence of the cloister the monk is called to spend a life of prayer, by day and by night, with prolonged and strict fasting; he must put into practice generous brotherly charity in ever prompt and willing obedience to the prior. In study and in the daily meditation of Sacred Scripture, Peter Damian discovered the mystical meaning of the word of God, finding in it nourishment for his spiritual life. In this regard he described the hermit’s cell as the “parlour in which God converses with men”. For him, living as a hermit was the peak of Christian existence, “the loftiest of the states of life” because the monk, now free from the bonds of worldly life and of his own self, receives “a dowry from the Holy Spirit and his happy soul is united with its heavenly Spouse” (Ep 18, 17; cf. Ep 28, 43 ff.). This is important for us today too, even though we are not monks: to know how to make silence within us to listen to God’s voice, to seek, as it were, a “parlour” in which God speaks with us: learning the word of God in prayer and in meditation is the path to life.

St. Francis de Sales, restoring the “universal call to holiness”

Denver, Colo., Jan 23, 2011 / 07:09 am (CNA/EWTN News).- On Jan. 24, during the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity that runs from Jan. 18-25, Catholics will celebrate the life of St. Francis de Sales. A bishop and Doctor of the Church, his preaching brought thousands of Protestants back to the Catholic fold, and his writings on the spiritual life have proved highly influential.

The paradoxical circumstances of Francis’ birth, in the Savoy region (now part of France) during 1567, sum up several contradictory tendencies of the Church during his lifetime. The reforms of the Council of Trent had purified the Church in important ways, yet Catholics and Protestants still struggled against one another – and against the temptations of wealth and worldly power.

Francis de Sales, a diplomat’s son, was born into aristocratic wealth and privilege. Yet he was born in a room that his family named the “St. Francis room” – where there hung a painting of that saint, renowned for his poverty, preaching in the wilderness. In later years, Francis de Sales would embrace poverty also; but early in his ministry, the faithful chided him for having an aristocratic manner.

In many ways, Francis’ greatest achievements – such as the “Introduction to the Devout Life,” an

innovative spiritual guidebook for laypersons, or his strong emphasis on the role of human love in Christian devotion – represent successful attempts to re-integrate seemingly disparate “worldly” and “spiritual” realities into one coherent vision of life.

Few people, however, would have predicted these achievements for Francis during his earlier years. As a young man, he studied rhetoric, the humanities, and law. He had his law degree by age 25, and was headed for a political career. All the while, he was keeping the depths of his spiritual life – such as his profound devotion to the Virgin Mary, and his resolution of religious celibacy – a secret from the world.

Eventually, however, the truth came out, and Francis clashed with his father, who had arranged a marriage for him. The Bishop of Geneva intervened on Francis’ behalf, finding him a position in the administration of the Swiss Church that led to his priestly ordination in 1593. He volunteered to lead a mission to bring Switzerland, dominated by Calvinist Protestantism, back to the Catholic faith.

Taking on a seemingly impossible task, with only one companion – his cousin – the new priest adopted a harsh but hopeful motto: “Apostles battle by their sufferings, and triumph only in death.” It would serve him well as he traveled through Switzerland, facing many Protestants’ indifference or hostility, and being attacked by wild animals and even would-be assassins.

Some of Francis’ hearers –even, for a time, John Calvin’s protege Theodore Beza– found themselves captivated by the thoughtful, eloquent and joyful manner of the priest who implored their reunion with the Church. But he had more success when he began writing out these sermons and exhortations, slipping them beneath the doors that had been closed against him.

This pioneering use of religious tracts proved surprisingly effective at breaking down the resistance of the Swiss Calvinists, and it is estimated that between 40,000 and 70,000 of them returned to the Church through his efforts. He also served as a spiritual director, both in person and through written correspondence, with the latter format inspiring the “Introduction to the Devout Life.”

In 1602, Francis was chosen to become the Bishop of Geneva, a position he did not seek or desire. Accepting the position, however, he gave the last twenty years of his life in ongoing sacrifice, for the restoration of Geneva’s churches and religious orders. He also helped one of his spiritual directees, the widow and future saint Jane Frances de Chantal, to found an order with a group of women.

Worn out by nearly thirty years of arduous travel and other burdens of Church leadership, Francis fell ill in 1622 while visiting one of a convent he had helped to found in Lyons. He died there, three days after Christmas that year. St. Francis de Sales was canonized in 1665, and honored as a Doctor of the Church in 1877.

Because of the crucial role of writing in his apostolate, St. Francis de Sales is the patron of writers and journalists. He is also widely credited with restoring, during his own day, a sense of what the Second Vatican Council would later call the “universal call to holiness” – that is, the notion that all people, not only those in formal religious life, are called to the heights of Christian sanctification. – CNA/EWTN News

A Prayer of St. Frances de Sales

Lord, I am yours,

and I must belong to no one but you.

My soul is yours,

and must live only by you.

My will is yours,

and must love only for you.

I must love you as my first cause,

since I am from you.

I must love you as my end and rest,

since I am for you.

I must love you more than my own being,

since my being subsists by you.

I must love you more than myself,

since I am all yours and all in you.

AMEN.

Meditations from the Introduction to the Devout Life by St. Francis de Sales

Pope St. Leo the Great…father of the church, doctor of the church, and so much more – Discerning Hearts

No one, however weak, is denied a share in the victory of the cross.

No one is beyond the help of the prayer of Christ.

– St. Leo the Great

How do you stop a barbarian invader like Attila from sacking your town? Pray, pray, pray…just ask St. Leo the Great.

Take a listen to Mike Aquilina (the “great” son of the Fathers) talk about St. Leo the Great:

Take a listen to Mike Aquilina (the “great” son of the Fathers) talk about St. Leo the Great:

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 17:52 — 16.4MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podchaser | Gaana | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | Anghami | RSS | More

CNA –Pope Leo the Great is the first Pope whose sermons and letters, many of which were on faith and charity, were preserved in extensive collections. He served as pontiff from 440 until his death in 461. His writing on the Incarnation was acclaimed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. –

Prior to his pontificate, Leo was a deacon and active as a peacemaker in the Roman Empire. He is most remembered for having successfully persuaded Attila the Hun not to plunder Rome. He was not as successful during

another attack three years later, however. Nevertheless, he managed to save the city from being burnt. He stayed on to help the people rebuild Rome.

He was made a Doctor of the Church in 1754-CNA

This is the chapel/altar area with the tomb of St. Leo in St. Peter’s in Rome. It was restricted to the public for some reason. But I was able to get close, because I went to confession in that area (a very interesting story I’ll share some day).

Here is the “great” painting by Raphael that is in the Vatican Museum of St. Leo imploring Attilia to back off and change his ways (and he did, go figure)

Spiritual Writings –

– Sermons

– Letters

St. Therese of Lisieux and the Little Way

VATICAN CITY, 6 APR 2011 (VIS) – In his general audience in St. Peter’s Square today, attended by more than 10,000 people, Benedict XVI dedicated his catechesis to St. Therese of Lisieux, or St. Therese of the Child Jesus and the Holy Face, “who lived in this world for only twenty-four years at the end of the nineteenth century, leading a very simple and hidden life, but who, after her death and the publication of her writings, became one of the best-known and loved saints”.

“Little Therese“, the Pope continued, “never failed to help the most simple souls, the little ones, the poor and the suffering who prayed to her, but also illuminated all the Church with her profound spiritual doctrine, to the point that the Venerable John Paul II, in 1997, granted her the title of Doctor of the Church … and described her as an ‘expert in scientia amoris’. Therese expressed this science, in which all the truth of the faith is revealed in love, in her autobiography ‘The Story of a Soul’, published a year after her death”.

Therese was born in 1873 in Alencon, France. She was the youngest of the nine children of Louis and Zelie Martin, and was beatified in 2008. Her mother died when she was four years old, and Therese later suffered from a serious nervous disorder from which she recovered in 1886 thanks to what she later described as “the smile of the Virgin”. In 1887 she made a pilgrimage to Rome with her father and sister, where she asked Leo XIII for permission to enter Carmel of Lisieux, at just fifteen years of age. Her wish was granted a year later; however, at the same time her father began to suffer from a serious mental illness, which led Therese to the contemplation of the Holy Face of Christ in his Passion. In 1890 she took her vows. 1896 marked the beginning of a period of great  physical and spiritual suffering, which accompanied her until her death.

physical and spiritual suffering, which accompanied her until her death.

In those moments, “she lived the faith at its most heroic, as the light in the shadows that invade the soul” the Pope said. In this context of suffering, living the greatest love in the littlest things of daily life, the Saint realised her vocation of becoming the love at the heart of the Church”.

She died in the afternoon of 30 September, 1897, uttering the simple words, “My Lord, I love You!”. “These last words are the key to all her doctrine, to her interpretation of the Gospel”, the Pope emphasised. “The act of love, expressed in her final breath, was like the continued breathing of the soul … The words ‘Jesus, I love You’ are at the centre of all her writings”.

St. Therese is “one of the ‘little ones’ of the Gospel who allow themselves to be guided by God, in the depth of His mystery. A guide for all, especially for… theologians. With humility and faith, Therese continually entered the heart of the Scriptures which contain the Mystery of Christ. This reading of the Bible, enriched by the science of love, does not oppose academic science. The ‘science of the saints’, to which she refers on the final page of ‘The Story of a Soul’, is the highest form of science”.

“In the Gospel, Therese discovers above all the Mercy of Jesus … and ‘Trust and Love’ are therefore the end point of her account of her life, two words that, like beacons, illuminated her saintly path, in order to guide others along the same ‘little way of trust and love’, of spiritual childhood. Her trust is like that of a child, entrusting herself to the hands of God, and inseparable from her strong, radical commitment to the true love that is the full giving of oneself”, the Holy Father concluded.

More on St. Therese can be found here

Also click here for a Novena to St. Therese

Saint Lawrence of Brindisi, preacher and architect of peace

VATICAN CITY, 23 MAR 2011 (VIS) – In his general audience this morning, Benedict XVI dedicated his catechesis to St. Lawrence of Brindisi (born Giulio Cesare Rossi, 1559-1619), a Doctor of the Church.

VATICAN CITY, 23 MAR 2011 (VIS) – In his general audience this morning, Benedict XVI dedicated his catechesis to St. Lawrence of Brindisi (born Giulio Cesare Rossi, 1559-1619), a Doctor of the Church.

The saint, who lost his father at the age of seven, was entrusted by his mother to the care of the Friars Minor Conventuals. He subsequently entered the Order of Capuchins and was ordained a priest in 1582. He acquired a profound knowledge of ancient and modern languages, thanks to which “he was able to undertake an intense apostolate among various categories of people“, the Pope explained. He was also an effective preacher well versed not only in the Bible but also in rabbinic literature, which he knew so well “that rabbis themselves were amazed and showed him esteem and respect”.

As a theologian and expert in Sacred Scripture and the Church Fathers, Lawrence of Brindisi was an exemplary teacher of Catholic doctrine among those Christians who, especially in Germany, had adhered to the Reformation. “With his clear and tranquil explanations he demonstrated the biblical and patristic foundation of all the articles of faith called into question by Martin Luther, among them the primacy of St. Peter and his Successors, the divine origin of the episcopate, justification as interior transformation of man, and the necessity of good works for salvation. The success enjoyed by St. Lawrence helps us to understand that even today, as the hope-filled journey of ecumenical dialogue continues, the reference to Sacred Scripture, read in the Tradition of the Church, is an indispensable element of fundamental importance”.

“Even the lowliest members of the faithful who did not possess vast culture drew advantage from the convincing words of St. Lawrence, who addressed the humble in order to call everyone to live a life coherent with the faith they professed”, said the Holy Father. “This was a great merit of the Capuchins and of the other religious orders which, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, contributed to the renewal of Christian life. … Even today, the new evangelisation needs well-trained, zealous and courageous apostles, so that the light and beauty of the Gospel may prevail over the cultural trends of ethical relativism and religious indifference, transforming the various ways people think and act in an authentic Christian humanism”.

Lawrence was a professor of theology, master of novices, minister provincial and minister general of the Capuchin Order, but amidst all these tasks “he also cultivated an exceptionally active spiritual life”, the Pope said. In this context he noted how all priests “can avoid the danger of activism – that is, of acting while forgetting the profound motivations of their ministry – only if they pay heed to their own inner lives”.

The Holy Father then turned his attention to another aspect of the saint’s activities: his work in favour of peace.  “Supreme Pontiffs and Catholic princes repeatedly entrusted him with important diplomatic missions to placate controversies and favour harmony between European States, which at the time were threatened by the Ottoman Empire. Today, as in St. Lawrence’s time, the world has great need of peace, it needs peace-loving and peace-building men and women. Everyone who believes in God must always be a source of peace and work for peace”, he said.

“Supreme Pontiffs and Catholic princes repeatedly entrusted him with important diplomatic missions to placate controversies and favour harmony between European States, which at the time were threatened by the Ottoman Empire. Today, as in St. Lawrence’s time, the world has great need of peace, it needs peace-loving and peace-building men and women. Everyone who believes in God must always be a source of peace and work for peace”, he said.

Lawrence of Brindisi was canonised in 1881 and declared a Doctor of the Church by Blessed John XXIII in 1959 in recognition of his many works of biblical exegesis and Mariology. In his writings, Lawrence “also highlighted the action of the Holy Spirit in the lives of believers”, the Pope said.

“St. Lawrence of Brindisi”, he concluded, “teaches us to love Sacred Scripture, to become increasingly familiar with it, daily to cultivate our relationship with the Lord in prayer, so that our every action, our every activity, finds its beginning and its fulfilment in Him”.

AG/ VIS 20110323 (650)

Published by VIS – Holy See Press Office – Wednesday, March 23, 2011

St. Francis de Sales: Great master of Spirituality and Peace

VATICAN CITY, 2 MAR 2011 (VIS) – During today’s general audience, which was held in the Paul VI Hall, the Pope spoke about St. Francis de Sales, bishop and doctor of the Church who lived in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Born in 1567 to a noble family in the Duchy of Savoy, while still very young Francis, “reflecting on the ideas of St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, underwent a profound crisis which led him to question himself about his own eternal salvation and about the destiny God had in store for him, experiencing the principle theological questions of his time as an authentic spiritual drama“. The saint “found peace in the radical and liberating truth of God’s love: loving Him without asking anything in return and trusting in divine love; this would be the secret of his life”.

Francis de Sales, the Holy Father explained, was ordained a priest in 1593 and consecrated as bishop of Geneva in 1602, “in a period in which the city was a stronghold of Calvinism. … He was an apostle, preacher, writer, man of action and of prayer; committed to realising the ideals of the Council of Trent, and involved in controversies and dialogue with Protestants. Yet, over and above the necessary theological debate, he also experienced the effectiveness of personal relations and of charity”.

With St. Jane Frances de Chantal he founded the Order of the Visitation, characterised “by a complete consecration to God lived in simplicity and humility“. St. Francis of Sales died in 1622.

In his book “An Introduction to the Devout Life”, the saint “made a call which may have appeared revolutionary at that time: the invitation to belong completely to God while being fully present in the world. … Thus arose that appeal to the laity, that concern for the consecration of temporal things and for the sanctification of daily life upon which Vatican Council II and the spirituality of our time have laid such emphasis”.

Referring then to the saint’s fundamental work, his “Treatise on the Love of God”, the Pope highlighted how “in a period of intense mysticism” it “was an authentic ‘summa’ and at the same time a fascinating literary work. … Following the model of Holy Scripture, St. Francis of Sales speaks of the union between God and man, creating a whole series of images of interpersonal relationships. His God is Father and Lord, Bridegroom and Friend”.

The treatise contains “a profound meditation on human will and a description of how it flows, passes and dies, in order to live in complete abandonment, not only to the will of God, but to what pleases Him, … to His pleasure. At the apex of the union with God, beyond the rapture of contemplative ecstasy, lies that well of concrete charity which is attentive to all the needs of others”.

Benedict XVI concluded his catechesis by noting that “in a time such as our own, which seeks freedom, … we must not lose sight of the relevance of this great master of spirituality and peace who gave his disciples the ‘spirit of freedom’, true freedom, at the summit of which is a fascinating and comprehensive lesson about the truth of love. St. Francis of Sales is an exemplary witness of Christian humanism. With his familiar style, with his parables which sometimes contain a touch of poetry, he reminds us that inscribed in the depths of man is nostalgia for God, and that only in Him can we find true joy and complete fulfilment”.

DOS#7 The Fifth Rule – Discernment of Spirits w/ Fr. Timothy Gallagher – Discerning Hearts Podcast

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 27:43 — 19.0MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podchaser | Gaana | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | Anghami | RSS | More

Episode 7 -The Fifth Rule:

In time of desolation never to make a change; but to be firm and constant in the resolutions and determination in which one was the day preceding such desolation, or in the determination in which he was in the preceding consolation. Because, as in consolation it is rather the good spirit who guides and counsels us, so in desolation it is the bad, with whose counsels we cannot take a course to decide rightly.

In this episode of the Discerning Hearts Podcast, Fr. Timothy Gallagher and Kris McGregor delve into St. Ignatius of Loyola’s fifth rule for the discernment of spirits, focusing on the importance of stability in one’s spiritual commitments during times of spiritual desolation. The discussion emphasizes not changing spiritual resolutions when experiencing desolation, as these periods are influenced negatively by the enemy.

Fr. Gallagher highlights the pivotal role of Rule Five, urging listeners to cling to their spiritual determinations when faced with the challenges posed by the enemy during desolation. Various scenarios illustrate how desolation can impact individuals, emphasizing the necessity of adhering to spiritual intentions set during times of consolation or tranquility.

The dialogue underscores the deceptive nature of the enemy in moments of spiritual desolation, illustrating how it can lead to doubt and discouragement. By referencing real-life examples and insights from St. Ignatius’s own experiences, Fr. Gallagher provides tangible guidance on recognizing and countering the enemy’s tactics, stressing the rule’s significance in maintaining spiritual direction and growth.

Listeners are encouraged to engage deeply with the content, reflecting on its relevance to their spiritual practices and challenges. The episode concludes with a call to further explore and apply Ignatius’s teachings, fostering a deeper understanding of discernment and spiritual resilience in the face of adversity.

Discerning Hearts Reflection Questions:

- Understanding Spiritual Desolation: Reflect on times when you’ve experienced spiritual desolation—those moments when you felt distant from God, devoid of consolation in prayer, or tempted to abandon your spiritual practices. Consider how these experiences align with Ignatius’s description of the enemy’s tactics during desolation.

- The Value of Spiritual Steadfastness: Meditate on the importance of being steadfast in your spiritual commitments, especially during challenging times. How have you responded to spiritual desolation in the past? Have you been tempted to make changes during these periods? Reflect on the consequences of these actions.

- The Role of the Enemy: Contemplate the idea that during times of spiritual desolation, the enemy tries to lead us away from God’s path. Consider how recognizing this can empower you to resist negative influences and stay true to your spiritual direction.

- Rule Five as a Lifeline: Think of Rule Five not just as a guideline, but as a lifeline during spiritual turmoil. In what ways can this rule provide you with a firm anchor in your spiritual life? How can it serve as a source of light when all seems dark?

- Application of Rule Five: Reflect on practical ways to apply Rule Five in your daily life. Whether it’s sticking to your prayer schedule, attending Mass, or fulfilling your role in ministry, consider how maintaining these commitments can fortify your spiritual resilience.

- Spiritual Growth through Adversity: Ponder the growth that can come from enduring spiritual desolation without making rash changes. How has your faith been tested and strengthened in such times?

- Seeking Guidance and Community: Reflect on the value of seeking guidance from spiritual directors, confessors, or trusted mentors during times of desolation. How can your faith community support you in remaining steadfast?

- Ignatian Spirituality as a Resource: Consider delving deeper into Ignatian spirituality to enhance your discernment skills. How can the principles and practices of this spiritual tradition enrich your relationship with God?

The Discernment of Spirits: Setting the Captives Free – Serves as an introduction to the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola

The 14 Rules for Discerning Spirits –

“The Different Movements Which Are Caused In The Soul”

as outlined by St. Ignatius of Loyola can be found here

Father Timothy M. Gallagher, O.M.V., was ordained in 1979 as a member of the Oblates of the Virgin Mary, a religious community dedicated to retreats and spiritual formation according to the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius. Fr. Gallagher is featured on the EWTN series “Living the Discerning Life: The Spiritual Teachings of St. Ignatius of Loyola”.

For more information on how to obtain copies of Fr. Gallaghers’s various books and audio which are available for purchase, please visit his website: www.frtimothygallagher.org

For the other episodes in this series visit

Fr. Timothy Gallagher’s “Discerning Hearts” page

St. Robert Bellarmine, doctor of the Church…”an outstanding figure of a troubled age”

“His ‘Controversial Works’ or ‘Disputationes’ are still a valid point of reference for Catholic ecclesiology”, said the Holy Father. “They emphasise the institutional aspect of the Church, in response to the errors then circulating on that topic. Yet Bellarmine also threw light on invisible aspects of the Church as Mystical Body, which he explained using the analogy of the body and soul, in order to describe the relationship between the interior richness of the Church and her visible exterior features.

“In this monumental work, which seeks to categorise the various theological controversies of the age, he avoids polemical and aggressive tones towards the ideas of the Reformation but, using the arguments of reason and of Church Tradition, clearly and effectively illustrates Catholic doctrine.

“Nonetheless”, the Pope added, “his true heritage lies in the way in which he conceived his work. His burden of office did not, in fact, prevent him from striving daily after sanctity through faithfulness to the requirements of his condition as religious, priest and bishop. … His preaching and catechesis reveal that same stamp of essentiality which he learned from his Jesuit education, being entirely focused on concentrating the power of the soul on the Lord Jesus, intensely known, loved and imitated”.

did not, in fact, prevent him from striving daily after sanctity through faithfulness to the requirements of his condition as religious, priest and bishop. … His preaching and catechesis reveal that same stamp of essentiality which he learned from his Jesuit education, being entirely focused on concentrating the power of the soul on the Lord Jesus, intensely known, loved and imitated”.

In another of his books, “De gemitu columbae” in which the Church is represented as a dove, Robert Bellarmine “forcefully calls clergy and faithful to a personal and concrete reform of their lives, in accordance with the teachings of Scripture and the saints. … With great clarity and the example of his own life, he clearly teaches that there can be no true reform of the Church unless this is first preceded by personal reform and conversion of heart on our part”.

“If you are wise, then understand that you were created for the glory of God and for your eternal salvation”, said the Pope quoting from one of the saint’s works. “Favourable or adverse circumstances, wealth and poverty, health and sickness, honour and offence, life and death, the wise must neither seek these things, nor seek to avoid them per se. They are good and desirable only if they contribute to the glory of God and to your eternal happiness, they are bad and to be avoided if they hinder this”.

The Pope concluded: “These words have not gone out of fashion, but should be meditated upon at length in order to guide our journey on this earth. They remind us that the goal of our life is the Lord. … They remind us of the importance of trusting in God, of living a life faithful to the Gospel, and of accepting all the circumstances and all actions of our lives, illuminating them with faith and prayer”.

Published by VIS – Holy See Press Office

St. Peter Canisius…”faithful to dogma, respectful to people”

VATICAN CITY, 9 FEB 2011 (VIS) – Benedict XVI dedicated his catechesis during this morning’s general audience to St. Peter Canisius, whom Leo XIII proclaimed as “the second apostle of Germany”, and who was subsequently canonised and proclaimed as a Doctor of the Church by Pius XI in 1925.

Born at Nijmegen in the Netherlands in 1521, Peter Canisius entered the Society of Jesus in 1543 and was ordained a priest in 1546. In 1548, St. Ignatius of Loyola sent him to complete his spiritual formation in Rome. A year later he moved to the Duchy of Bavaria where he became dean and rector of the University of Ingolstadt. Later he was administrator of the diocese of Vienna, Austria, where he practiced his pastoral ministry in hospitals and prisons. In the year 1566 he founded the College of Prague and, until 1569, was the first superior of the Jesuit province of upper Germany.

In this role he created a network of Jesuit communities in Germanic countries, especially schools, which became starting points for the Catholic Reformation. He participated in religious discussions with Protestant leaders, including Melanchthon, held in the city of Worms, acted as pontifical nuncio to Poland, participated in the two Diets of Augsburg in 1559 and in 1565, and attended the closing session of the Council of Trent. In 1580 he retired to Fribourg in Switzerland where he dedicated himself to writing and where he died in 1597. Peter Canisius also edited the complete works of Cyril of Alexandria and of St. Leo the Great, and the Letters of St. Jerome.

Among his most famous works were his three “Catechises”, written between 1555 and 1558. The first was aimed at students capable of understanding the basic notions of theology; the second at ordinary young people for their primary religious education; and the third at children with a medium- or secondary-school education.

“One characteristic of St. Peter Canisius”, said the Holy Father, was “that he was able to harmonise fidelity to dogmatic principles with the respect due to each individual. … In a historical period of deep confessional contrasts, he avoided severity and the rhetoric of anger, something fairly rare in discussions among Christians at that time, … and sought only to explain our spiritual roots and to revitalise faith in the Church”.

“In the works destined for the spiritual education of the masses, our saint insists on the importance of the liturgy, … the rites of Mass and the other Sacraments. However, at the same time, he is careful to show the faithful the importance and beauty of individual daily prayer to accompany and permeate participation in the Church’s public worship”, said Benedict XVI, pointing our that “this exhortation and this methodology maintain all their value, especially after being authoritatively re-presented by Vatican Council II”.

Peter Canisius “clearly teaches that apostolic ministry is incisive and produces fruits of salvation in people’s hearts only if the preacher is a personal witness of Jesus and knows how to become His instrument, closely bound to Him through faith in His Gospel and in His Church, through a morally coherent life and incessant prayer”. AG/VIS 20110209 (530)

St. Hilary of Poitiers, Father and Doctor of the Church…defender of the Blessed Trinity

Born of wealthy polytheistic, pagan nobility, Hilary’s early life was uneventful as he married, had children (including Saint Abra), and studied on his own. Through his studies he came to believe in salvation through good works, then monotheism. As he studied the Bible for the first time, he literally read himself into the faith, and was converted by the end of the New Testament.

Hilary lived the faith so well he was made bishop of Poitiers from 353 to 368. Hilary opposed the emperor’s attempt to run Church matters, and was exiled; he used the time to write works explaining the faith. His teaching and writings converted many, and in an attempt to reduce his notoriety he was returned to the small town of Poitiers where his enemies hoped he would fade into obscurity. His writings continued to convert pagans.