From Vatican.va (the extended version translated into English from the Italian)

From Vatican.va (the extended version translated into English from the Italian)

GENERAL AUDIENCE

(the fuller catechesis translated into English from the Italian text)

Dear brothers and sisters,

In the two previous catechesis we thought that prayer is a universal phenomenon, which – although in different forms – is present in the cultures of all time.

Today instead I would like to start out on a biblical path on this topic which will guide us to deepening the dialogue of the Covenant between God and man, which enlivened the history of salvation to its culmination, to the definitive Word that is Jesus Christ.

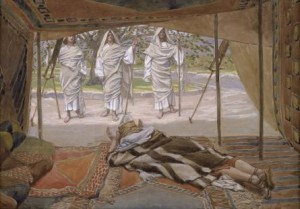

This path will lead us to reflect on certain important texts and paradigmatic figures of the Old and New Testaments. It will be Abraham the great Patriarch, the father of all believers (cf. Rom 4:11-12, 16-17), to offer us a first example of prayer in the episode of intercession for the cities of Sodom and Gomorrah.

And I would also like to ask you to benefit from the journey we shall be making in the forthcoming catecheses to become more familiar with the Bible, which I hope you have in your homes and, during the week, to pause to read it and to meditate upon it in prayer, in order to know the marvellous history of the relationship between God and man, between God who communicates with us and man who responds, who prays.

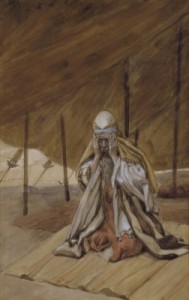

The first text on which we shall reflect is in chapter 18 of the Book of Genesis. It is recounted that the evil of the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah had reached the height of depravity so as to require an intervention of God, an act of justice, that would prevent the evil from destroying those cities.

It is here that Abraham comes in, with his prayer of intercession. God decides to reveal to him what is about to happen and acquaints him with the gravity of the evil and its terrible consequences, because Abraham is his chosen one, chosen to become a great people and to bring the divine blessing to the whole world. His is a mission of salvation which must counter the sin that has invaded human reality; the Lord wishes to bring humanity back to faith, obedience and justice through Abraham. And now this friend of God seeing the reality and neediness of the world, prays for those who are about to be punished and begs that they be saved.

about to happen and acquaints him with the gravity of the evil and its terrible consequences, because Abraham is his chosen one, chosen to become a great people and to bring the divine blessing to the whole world. His is a mission of salvation which must counter the sin that has invaded human reality; the Lord wishes to bring humanity back to faith, obedience and justice through Abraham. And now this friend of God seeing the reality and neediness of the world, prays for those who are about to be punished and begs that they be saved.

Abraham immediately postulates the problem in all its gravity and says to the Lord: “Will you indeed destroy the righteous with the wicked? Suppose there are fifty righteous within the city; will you then destroy the place and not spare it for the fifty righteous who are in it? Far be it from you to do such a thing, to slay the righteous with the wicked, so that the righteous fare as the wicked! Far be that from you! Shall not the Judge of all the earth do right?” (Gen 18: 23-25).

Speaking these words with great courage, Abraham confronts God with the need to avoid a perfunctory form of justice: if the city is guilty it is right to condemn its crime and to inflict punishment, but — the great Patriarch affirms — it would be unjust to punish all the inhabitants indiscriminately. If there are innocent people in the city, they must not be treated as the guilty. God, who is a just judge, cannot act in this way, Abraham says rightly to God.

However, if we read the text more attentively we realize that Abraham’s request is even more pressing and more profound because he does not stop at asking for salvation for the innocent. Abraham asks forgiveness for the whole city and does so by appealing to God’s justice; indeed, he says to the Lord: “Will you then destroy the place and not spare it for the fifty righteous who are in it?” (v. 24b).

In this way he brings a new idea of justice into play: not the one that is limited to punishing the guilty, as men do, but a different, divine justice that seeks goodness and creates it through forgiveness that transforms the sinner, converts and saves him. With his prayer, therefore, Abraham does not invoke a merely compensatory form of justice but rather an intervention of salvation which, taking into account the innocent, also frees the wicked from guilt by forgiving them.

Abraham’s thought, which seems almost paradoxical, could be summed up like this: obviously it is not possible to treat the innocent as guilty, this would be unjust; it would be necessary instead to treat the guilty as innocent, putting into practice a “superior” form of justice, offering them a possibility of salvation because, if evildoers accept God’s pardon and confess their sin, letting themselves be saved, they will no longer continue to do wicked deeds, they too will become righteous and will no longer deserve punishment.

It is this request for justice that Abraham expresses in his intercession, a request based on the certainty that the Lord is merciful. Abraham does not ask God for something contrary to his essence, he knocks at the door of God’s heart knowing what he truly desires.

Sodom, of course, is a large city, 50 upright people seem few, but are not the justice and forgiveness of God perhaps proof of the power of goodness, even if it seems smaller and weaker than evil? The destruction of Sodom must halt the evil present in the city, but Abraham knows that God has other ways and means to stem the spread of evil. It is forgiveness that interrupts the spiral of sin and Abraham, in his dialogue with God, appeals for exactly this. And when the Lord agrees to forgive the city if 50 upright people may be found in it, his prayer of intercession begins to reach the abysses of divine mercy.

God perhaps proof of the power of goodness, even if it seems smaller and weaker than evil? The destruction of Sodom must halt the evil present in the city, but Abraham knows that God has other ways and means to stem the spread of evil. It is forgiveness that interrupts the spiral of sin and Abraham, in his dialogue with God, appeals for exactly this. And when the Lord agrees to forgive the city if 50 upright people may be found in it, his prayer of intercession begins to reach the abysses of divine mercy.

Abraham — as we remember — gradually decreases the number of innocent people necessary for salvation: if 50 would not be enough, 45 might suffice, and so on down to 10, continuing his entreaty, which became almost bold in its insistence: “suppose 40… 30… 20… are found there” (cf. vv. 29, 30, 31, 32). The smaller the number becomes, the greater God’s mercy is shown to be. He patiently listens to the prayer, he hears it and repeats at each supplication: “I will spare… I will not destroy… I will not do it” (cf. vv. 26,28, 29, 30, 31, 32).

Thus, through Abraham’s intercession, Sodom can be saved if there are even only 10 innocent people in it.

This is the power of prayer. For through intercession, the prayer to God for the salvation of others, the desire for salvation which God nourishes for sinful man is demonstrated and expressed. Evil, in fact, cannot be accepted, it must be identified and destroyed through punishment: The destruction of Sodom had exactly this function.

Yet the Lord does not want the wicked to die, but rather that they convert and live (cf. Ez 18:23; 33:11); his desire is always to forgive, to save, to give life, to transform evil into good. Well, it is this divine desire itself which becomes in prayer the desire of the human being and is expressed through the words of intercession.

With his entreaty, Abraham is lending his voice and also his heart, to the divine will. God’s desire is for mercy and love as well as his wish to save; and this desire of God found in Abraham and in his prayer the possibility of being revealed concretely in human history, in order to be present wherever there is a need for grace. By voicing this prayer, Abraham was giving a voice to what God wanted, which was not to destroy Sodom but to save it, to give life to the converted sinner.

This is what the Lord desires and his dialogue with Abraham is a prolonged and unequivocal demonstration of his merciful love. The need to find enough righteous people in the city decreases and in the end 10 were to be enough to save the entire population.

The reason why Abraham stops at 10 is not given in the text. Perhaps it is a figure that indicates a minimum community nucleus (still today, 10 people are the necessary quorum for public Jewish prayer). However, this is a small number, a tiny particle of goodness with which to start in order to save the rest from a great evil.

minimum community nucleus (still today, 10 people are the necessary quorum for public Jewish prayer). However, this is a small number, a tiny particle of goodness with which to start in order to save the rest from a great evil.

However, not even 10 just people were to be found in Sodom and Gomorrah so the cities were destroyed; a destruction paradoxically deemed necessary by the prayer of Abraham’s intercession itself. Because that very prayer revealed the saving will of God: the Lord was prepared to forgive, he wanted to forgive but the cities were locked into a totalizing and paralyzing evil, without even a few innocents from whom to start in order to turn evil into good.

This the very path to salvation that Abraham too was asking for: being saved does not mean merely escaping punishment but being delivered from the evil that dwells within us. It is not punishment that must be eliminated but sin, the rejection of God and of love which already bears the punishment in itself.

The Prophet Jeremiah was to say to the rebellious people: “Your wickedness will chasten you, and your apostasy will reprove you. Know and see that it is evil and bitter for you to forsake the Lord your God” (Jer 2:19).

It is from this sorrow and bitterness that the Lord wishes to save man, liberating him from sin. Therefore, however, a transformation from within is necessary, some foothold of of goodness, a beginning from which to start out in order to change evil into good, hatred into love, revenge into forgiveness.

For this reason there must be righteous people in the city and Abraham continuously repeats: “suppose there are…”. “There”: it is within the sick reality that there must be that seed of goodness which can heal and restore life. It is a word that is also addressed to us: so that in our cities the seed of goodness may be found; that we may do our utmost to ensure that there are not only 10 upright people, to make our cities truly live and survive and to save ourselves from the inner bitterness which is the absence of God. And in the unhealthy situation of Sodom and Gomorrah that seed of goodness was not to be found.

Yet God’s mercy in the history of his people extends further. If in order to save Sodom 10 righteous people were necessary, the Prophet Jeremiah was to say, on behalf of the Almighty, that only one upright person was necessary to save Jerusalem: “Run to and fro through the streets of Jerusalem, look and take note! Search her squares to see if you can find a man, one who does justice and seeks truth; that I may pardon her” (5:1).

The number dwindled further, God’s goodness proved even greater. Nonetheless this did not yet suffice, the superabundant mercy of God did not find the response of goodness that he sought, and under the siege of the enemy Jerusalem fell.

The number dwindled further, God’s goodness proved even greater. Nonetheless this did not yet suffice, the superabundant mercy of God did not find the response of goodness that he sought, and under the siege of the enemy Jerusalem fell.