Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 25:18 — 17.5MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podchaser | Gaana | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | Anghami | RSS | More

The Immaculate Conception – Building a Kingdom of Love with Msgr. John Esseff

On the the Solemnity of the Immaculate Conception, Msgr. Esseff reflects on the significance of the Immaculate Conception of Mary within the broader plan of salvation history. He uses Genesis, Ephesians, and the Gospel of Luke to show us God’s eternal plan to reconcile humanity with Himself through Jesus Christ. Humanity’s fall through Adam and Eve introduced sin and death into the world, but God’s response was the plan of redemption, preordained before creation, culminating in the birth of Christ. Mary, conceived without sin, is presented as the new Eve, uniquely chosen to bring Jesus into the world. Her “yes” to the angel Gabriel is seen as a pivotal moment in God’s plan, countering the disobedience of the first parents and initiating the ultimate defeat of sin, Satan, and death.

Through Jesus’ suffering, death, and resurrection, humanity is adopted as children of God and incorporated into Christ’s body, the Church. He encourages us to see the Immaculate Conception as a profound reminder of God’s love and the invitation to holiness.

Discerning Hearts Reflection Questions

- How does reflecting on God’s plan for redemption before creation deepen your trust in His providence?

- In what ways can recognizing the effects of original sin in your life inspire a greater appreciation for Christ’s saving work?

- How does the Immaculate Conception help you understand Mary’s unique role in God’s plan and her intercession for you?

- What does it mean to you personally to be adopted into God’s family through Jesus Christ?

- How can you live more fully as a member of Christ’s body, united with Him and His Church?

- In this Advent season, how are you preparing your heart to welcome Christ more fully into your life?

- How do you experience the Holy Spirit working in your life to bring about holiness and transformation?

- How can Mary’s fiat, her “yes” to God, inspire you to trust and surrender to His will in your own life?

Reading 1: Gn 3:9-15, 20

“After the man, Adam, had eaten of the tree,

the LORD God called to the man and asked him, “Where are you?”

He answered, “I heard you in the garden;

but I was afraid, because I was naked,

so I hid myself.”

Then he asked, “Who told you that you were naked?

You have eaten, then,

from the tree of which I had forbidden you to eat!”

The man replied, “The woman whom you put here with me

she gave me fruit from the tree, and so I ate it.”

The LORD God then asked the woman,

“Why did you do such a thing?”

The woman answered, “The serpent tricked me into it, so I ate it.”Then the LORD God said to the serpent:

“Because you have done this, you shall be banned

from all the animals

and from all the wild creatures;

on your belly shall you crawl,

and dirt shall you eat

all the days of your life.

I will put enmity between you and the woman,

and between your offspring and hers;

he will strike at your head,

while you strike at his heel.”The man called his wife Eve,

because she became the mother of all the living.”

Reading 2 Eph 1:3-6, 11-12

Brothers and sisters:

Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ,

who has blessed us in Christ

with every spiritual blessing in the heavens,

as he chose us in him, before the foundation of the world,

to be holy and without blemish before him.

In love he destined us for adoption to himself through Jesus Christ,

in accord with the favor of his will,

for the praise of the glory of his grace

that he granted us in the beloved.

In him we were also chosen,

destined in accord with the purpose of the One

who accomplishes all things according to the intention of his will,

so that we might exist for the praise of his glory,

we who first hoped in Christ.

Gospel: Lk 1:26-38

“The angel Gabriel was sent from God

to a town of Galilee called Nazareth,

to a virgin betrothed to a man named Joseph,

of the house of David,

and the virgin’s name was Mary.

And coming to her, he said,

“Hail, full of grace! The Lord is with you.”

But she was greatly troubled at what was said

and pondered what sort of greeting this might be.

Then the angel said to her,

“Do not be afraid, Mary,

for you have found favor with God.

Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son,

and you shall name him Jesus.

He will be great and will be called Son of the Most High,

and the Lord God will give him the throne of David his father,

and he will rule over the house of Jacob forever,

and of his Kingdom there will be no end.”

But Mary said to the angel,

“How can this be,

since I have no relations with a man?”

And the angel said to her in reply,

“The Holy Spirit will come upon you,

and the power of the Most High will overshadow you.

Therefore the child to be born

will be called holy, the Son of God.

And behold, Elizabeth, your relative,

has also conceived a son in her old age,

and this is the sixth month for her who was called barren;

for nothing will be impossible for God.”

Mary said, “Behold, I am the handmaid of the Lord.

May it be done to me according to your word.”

Then the angel departed from her.”

Lectionary for Mass for Use in the Dioceses of the United States, second typical edition, Copyright © 2001, 1998, 1997, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine

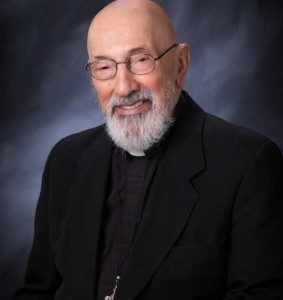

Msgr. John A. Esseff is a Roman Catholic priest in the Diocese of Scranton. Msgr. Esseff served as a retreat director and confessor to St. Teresa of Calcutta. He continues to offer direction and retreats for the sisters of the Missionaries of Charity around the world. Msgr. Esseff encountered St. Padre Pio, who would become a spiritual father to him. He has lived in areas around the world, serving in the Pontifical missions, a Catholic organization established by Pope St. John Paul II to bring the Good News to the world, especially to the poor. Msgr. Esseff assisted the founders of the Institute for Priestly Formation and continues to serve as a spiritual director for the Institute. He continues to serve as a retreat leader and director to bishops, priests and sisters and seminarians, and other religious leaders around the world.

Episode 6 – Marcion – Villains of the Early Church with Mike Aquilina

Episode 6 – Marcion – Villains of the Early Church with Mike Aquilina

Discerning Hearts Reflection Questions:

Discerning Hearts Reflection Questions: